Museums are paying more attention to their workplace practices. Can "responsiveness" succeed where "employee engagement" hasn't? Here are lessons from the 2017 Responsive Conference.

I attended the two-day Responsive Conference at New York City's Museum of the Moving Image last week, not sure what to expect—I've been to museum conferences, tech conferences, museum-tech conferences, publishing conferences, and museum publishing conferences, but this was my first conference dedicated to organizational culture.

What I wanted to figure out was how to improve upon the long-promised panacea of "employee engagement," which has never failed to get a mix of friendly, non-committal nods and shruggy yawns when I've used it in workplace conversation. The problem has always been that, to paraphrase Bobbie Fleckman in 'This Is Spinal Tap', "Sustainable working conditions with livable wages and benefits talk and jargon walks." The idea of employee engagement foundered against a lack of change and workplace improvement? Could anything, especially another jargony conference title, help?

What I found instead was an interesting mix of big-business realities, motivational psychology, startup disruption, tech-behemoth wisdom and failures, nonprofit mission-driven zeal, vulnerability workshopping, and some interpretive dance. Oh, and Muppets.

Kermit, now in I've-already-finished-that-thing-I-was-typing-so-hard-to-get-done form (taken at The Museum of the Moving Image)

People who know me (or who have read this blog, or followed me on Twitter) know that I've been trying for a while to create that Venn-diagram intersection of cultural organizations—especially museums—and organizational culture practitioners, to get museums to take advantage of the evolutionary workplace practices being pushed by org culture companies or more progressive divisions inside current institutions. Design Thinking has been the most successful version of this movement at reaching into museums. Other flavors (read the Responsive.org manifesto for a description of this conference's raison d'être, but most of org culture variations have significant overlap related to organizations being able to listen, learn, experiment, and develop humanistic and internally- and externally-aligned missions) haven't quite made the same inroads, perhaps due to budgets, unfamiliarity, or the sometimes-split between curatorial and business culture inside the museum; maybe the alignment is easier at startups or large legacy companies with room for internal experimentation. Entire blogs are dedicated to the obstacles that museum staff have in staying and thriving in the field, just as many industries face general issues in keeping staff happy (whatever that means). The current socio-political climate and the need for resistance don't make workplace satisfaction any easier.

What everyone at the Responsive Conference had in common was the idea of being a "change agent," someone who had the tools, motivation, mission, and belief to try to push for improvement of their organization or to be an expert at doing so for other institutions. (For the purposes of this article, I'm going to assume that change in an institution, in response to pressures from workplace conditions, community access, and other factors, and not just change for its own sake, is a good thing; read some interesting twitter conversations about change in museums here and here.)

Rather than try to recap the whole conference, let me provide ten takeaways:

1. Org change is a big and amorphous community. There's no clear definition of Responsiveness, no single vision, no single practice. If you're coming from the museum field it might be hard to pin down what makes a practice "responsive." It's like the entire industry is a start-up (and I'm not just talking "disruption"). What's important is that everyone wants companies to be better and working, learning, and organizing—and to do so with evidence. The ecosystem is a mix of small firms, freelance consultants, and large companies which have had the internal space to experiment, such as Pepsi and Airbnb. There's also more than a bit of the lifehacking and self-actualization in the air here.

"'Change agent'? Yep, I want to change my agent for putting me on this dumb show!" (taken at The Museum of the Moving Image, made-up dialogue mine …)

2. There's a LOT of terminology here. Emergent organization, adaptive workplace, learning organization, teal, responsive, open, deliberately developmental organization, sustainable work—the list goes on. Of course, many fields have expansive pedagogy like this, especially in their infancy, but this slippery lexicon can make it harder to sell colleagues and museum leaders on taking a chance on this kind of work. I've only recently started using the phrase "organization design" rather than "organizational culture," though you won't see it yet on my website. And calling yourself a "change agent" is great … among friends.

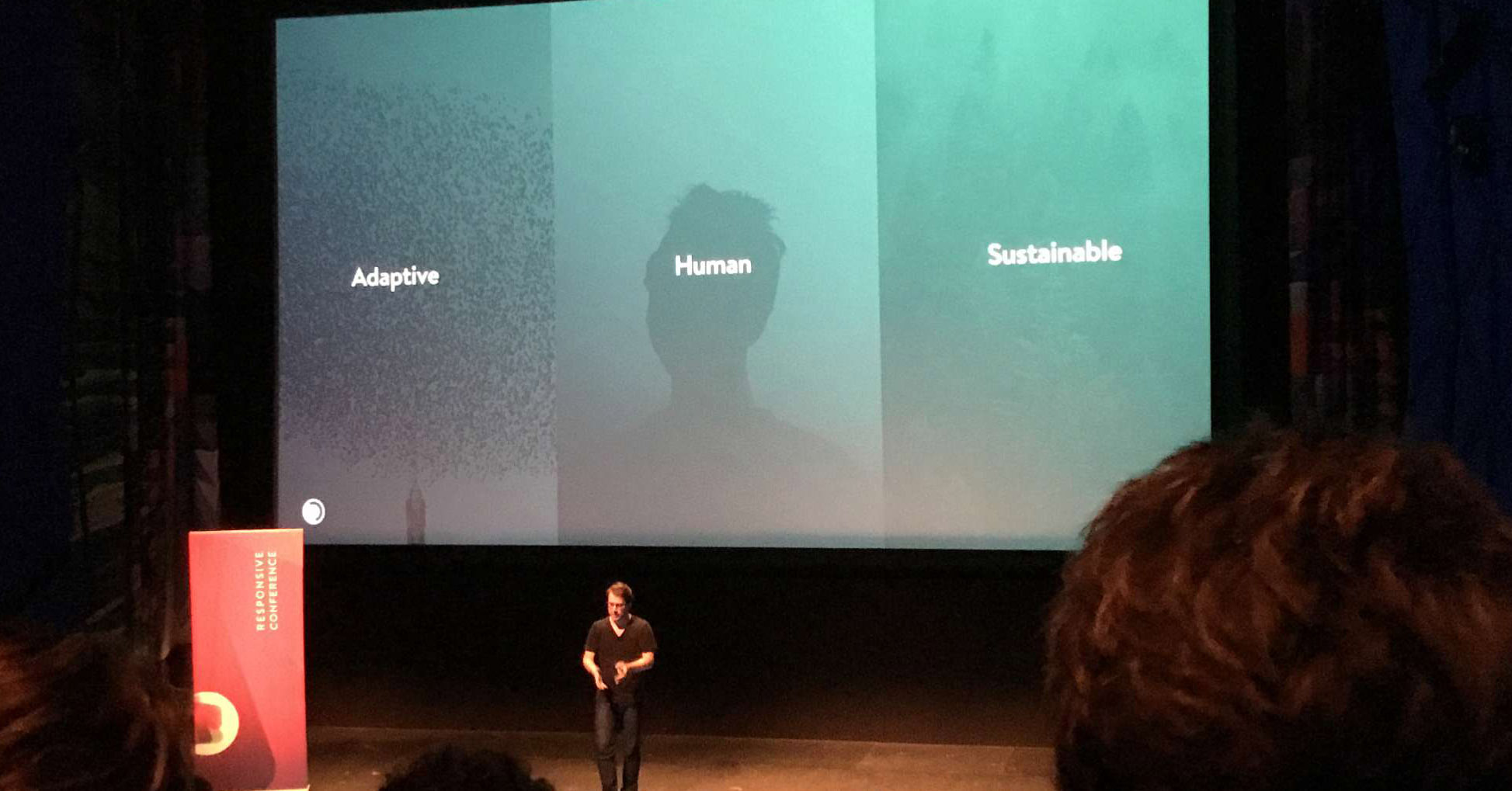

Words to change work by (author's photo of The Ready's Aaron Dignan during the conference keynote)

3. And yet, there's a great fit between responsive orgs and museums. Hope springs eternal. The Museum Computer Network's 2016 conference's theme was The Human-Centered Museum (my recap here, read others here), and many institutions (my Met included) are looking at how to be respectful of staff's intrinsic goals for work. (I'll avoid the term "work-life balance" because it's really about providing a better work-work balance—between work that's great and work that sucks; as in, as little of the latter as possible.) There wasn't a single moment at the Responsive Conference where I didn't understand what people wanted to accomplish. There was even a small unconference run by Kappie Farrington of the Rockefeller Foundation, discussing responsiveness in arts nonprofits—she used the term "social entrepreneurship," which I thought was great. (And in an interesting sidebar to the discussion about museums and neutrality, it was noted at the unconference that some museums might be worried about political stances because it could be used as a weapon to threaten their nonprofit status.)

R2D2 in bag form shows we're all people (slide from conference closing talk by Pam Slim, author of Escape from Cubicle Nation among other works, blogger, business and life-coaching consultant, and organizer of a local community business incubator in her small hometown)

4. There's something to be said for disruption through starting something new. Two speakers from relatively-new charity groups—Charles Best of school-focused DonorsChoose.org and Lauren Letta of developing-world-water-scarcity disruptors charity:water were involved in founding nonprofits and said that creating progressive workplace practices was much easier for them because these were company priorities from the beginning. Their external and internal practices could be aligned from the start. What I think that means for people in museums—especially large ones with legacy practices—is that you might have better success starting something new internally rather than trying to remake longstanding ways of working.

Good workplace practices, a good cause (Lauren Letta of charity:water talks with The Ready's Chris Murchison)

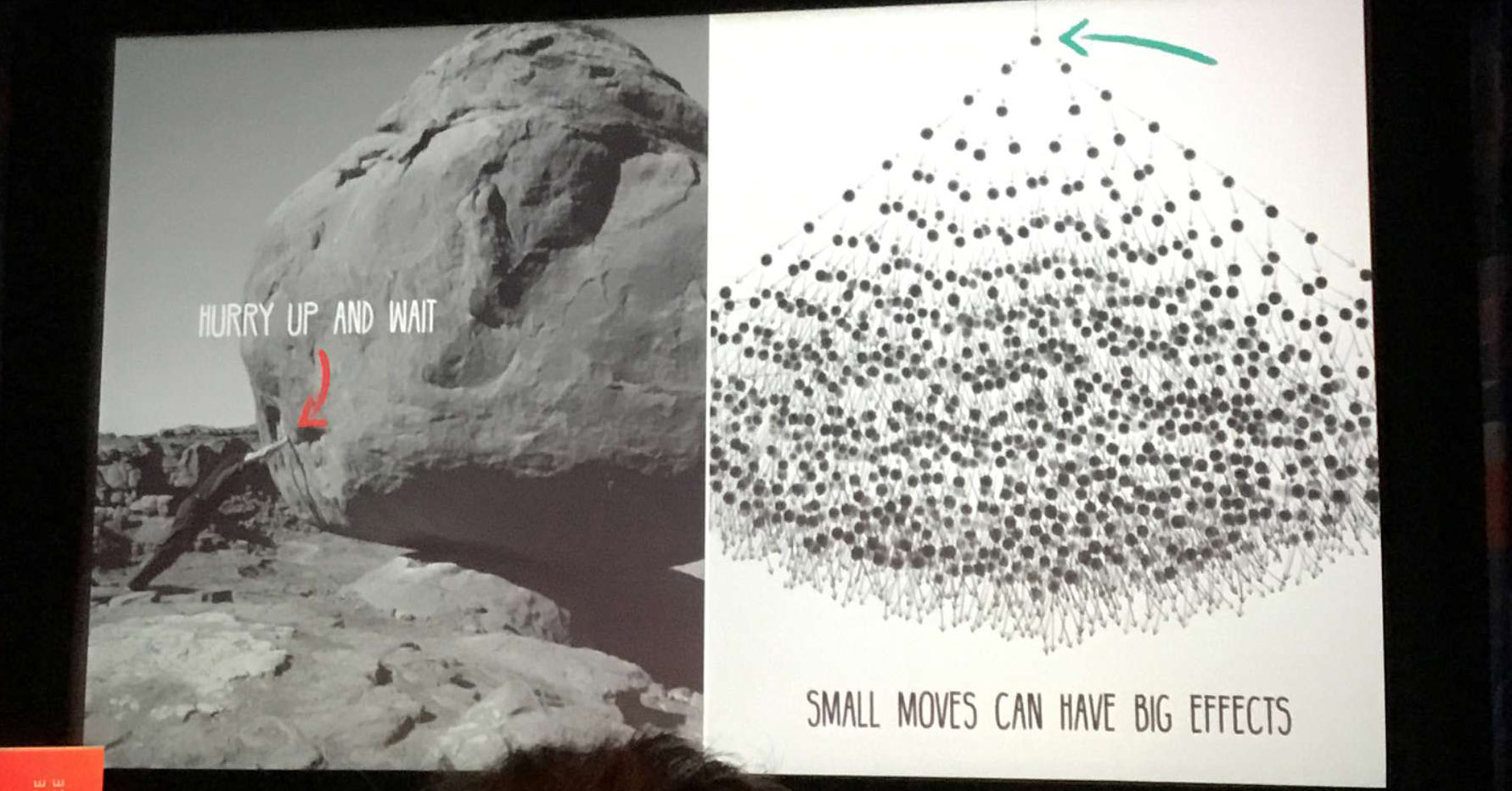

5. Big things start with small wins. Whether they were charities which started small or very big companies like Pepsi and Airbnb, all of these companies practiced the idea of getting to workplace transformation through small wins—achievable goals which can be replicated, tested, learned from, and used to provide inspiration to others. In my own work at the Met, I've often been counseled to describe the small wins me and my colleagues have achieved—like reorganizing our main publications server which made later archiving efforts much easier—than enormous undertakings like rebooting our label workflow.

You always have to start small (from Dignan's opening keynote presentation)

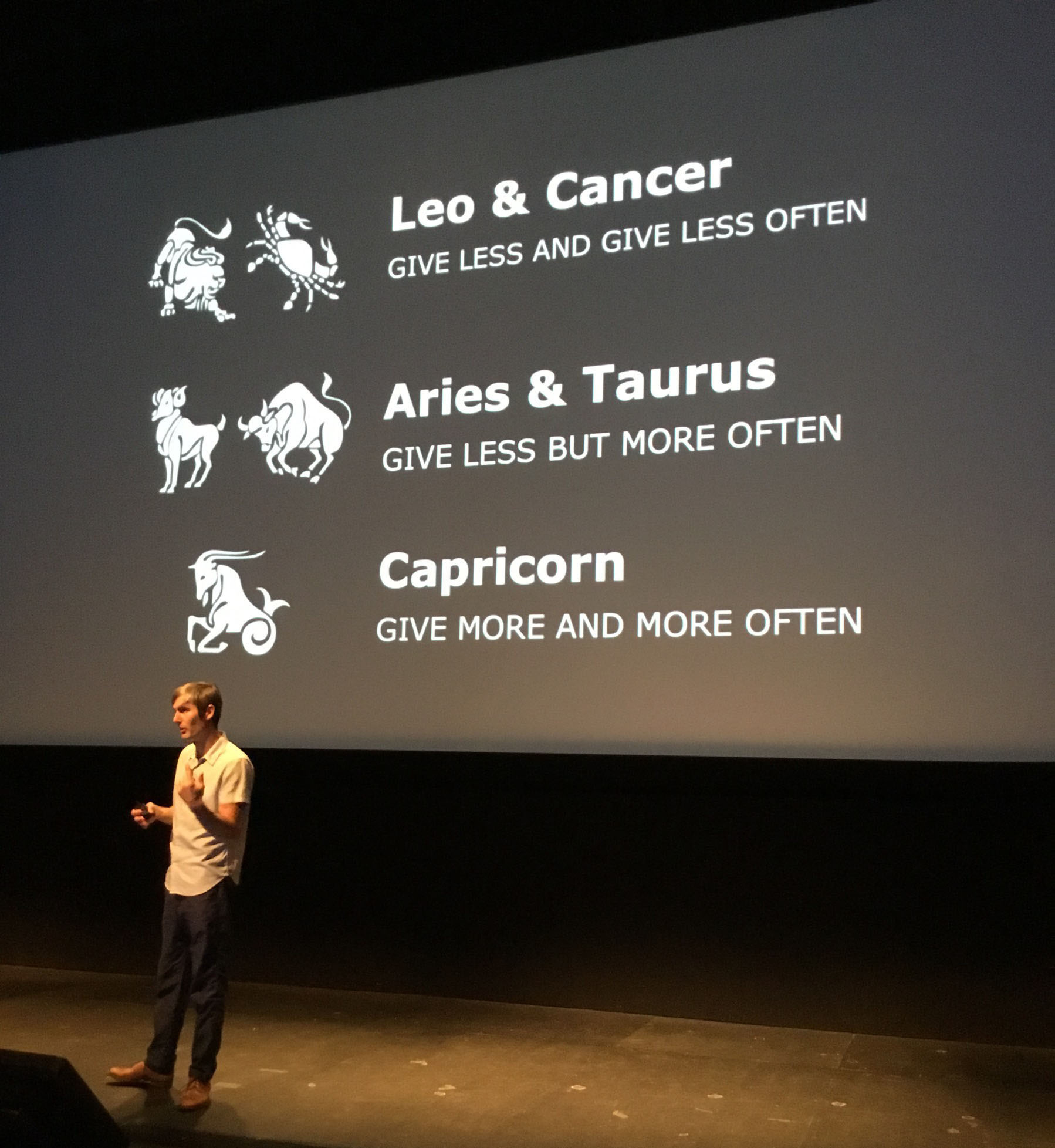

6. Experiment, experiment, experiment. If you're not trying things, you're going to fail at change. Charles Best of DonorsChoose described a/b/c tests to determine when different kinds of contributors are most likely to donate, and Lauren Letta of charity:water said that the charity constantly adjusted their workplace practices around roles, titles, and organization—and changing when it was clearly wrong. They don't practice culture fit in terms of what kinds of people they hire, but they make sure that potential employees can work within a changing organizational structure. At a chat with Lauren and with moderator Chris Murchison, we unpacked the term "excellence," which is good in theory but too often gets used internally as an exclusionary word, more on par with "perfect is the enemy of the good."

"For this, we have no explanation!"

"For this, we have no explanation!"

(Charles Best of DonorsChoose on some of the more unusual and surprising data his organization got and tested)

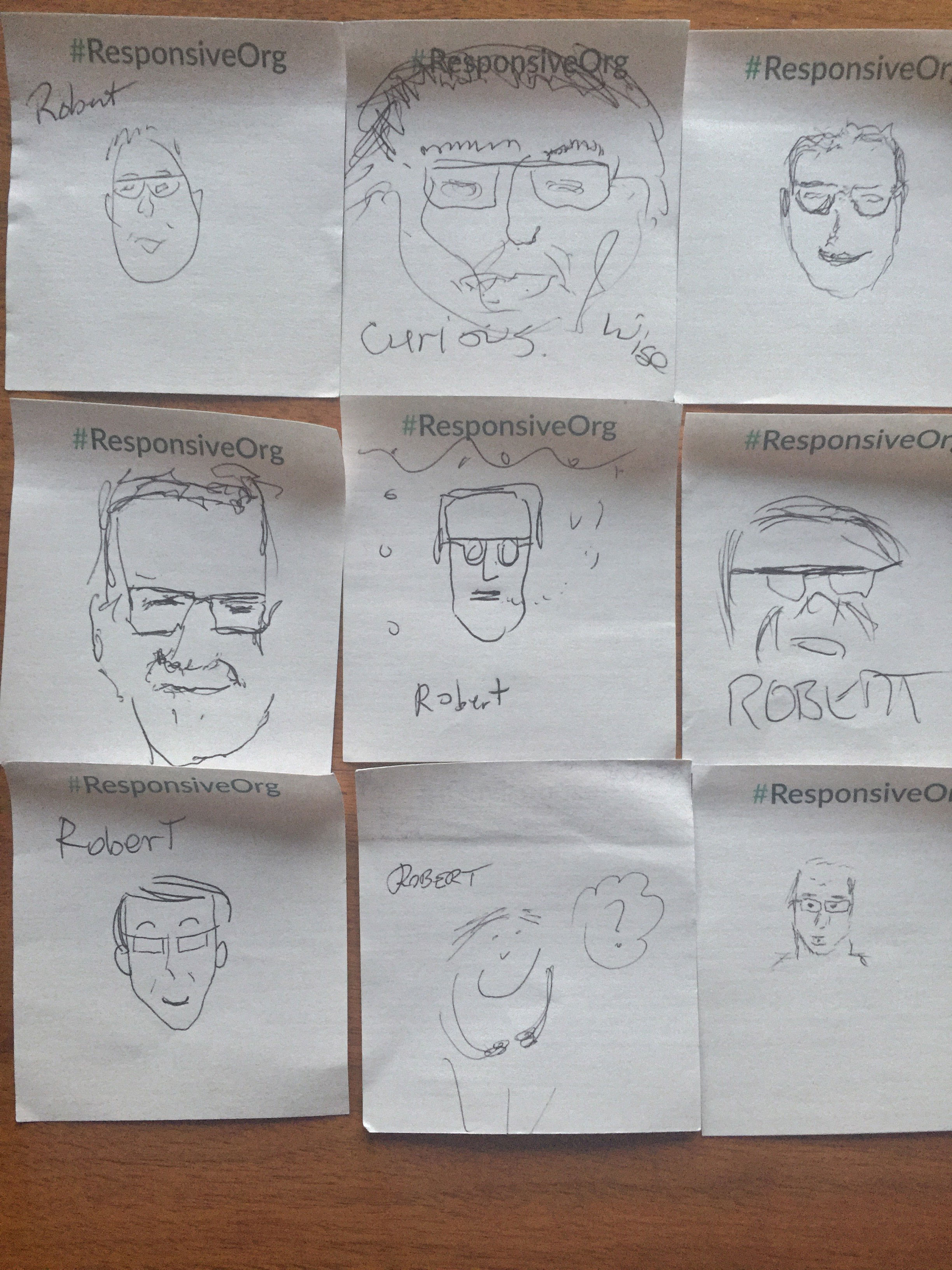

7. It's storytelling all the way down. Something every speaker emphasized was the importance of telling good stories—obviously as part of the selling of an institution to potential customers or audiences, but also internally, to staff. That's the aim of culture fit, to have internal narratives which make sense to everyone, and that you have staff capable of respecting these narratives, or you're going to find your people working at cross purposes—with tension and undercutting of efforts—before too long. I went to a workshop on the second day called "Fostering Learning Within Organizations," and the first half hour involved drawing 30-second sketches of other attendees faces on stickies. This strange-seeming exercise actually created an area of psychological safety, trust, and vulnerability, and took away expertise and authority. The perfection that so many of us are so invested in was impossible in this setting, and with these barriers to openness broken down, we discussed personal moments of learning—complete with very personal stories. In an environment where it's safe to ask questions, to make mistakes, and to be “bad” when you’re supposed to be excellent, we took a step back from authority—one of the people used the term “creative courage.” I can't swear this exercise would work great in a museum setting, but I do dream of this kind of openness in my workplace.

Your blogger, in learning-moment-exercise-form … (credit my many workshop co-participants who shall remain anonymous—but rest assured their sketching was much better than mine!)

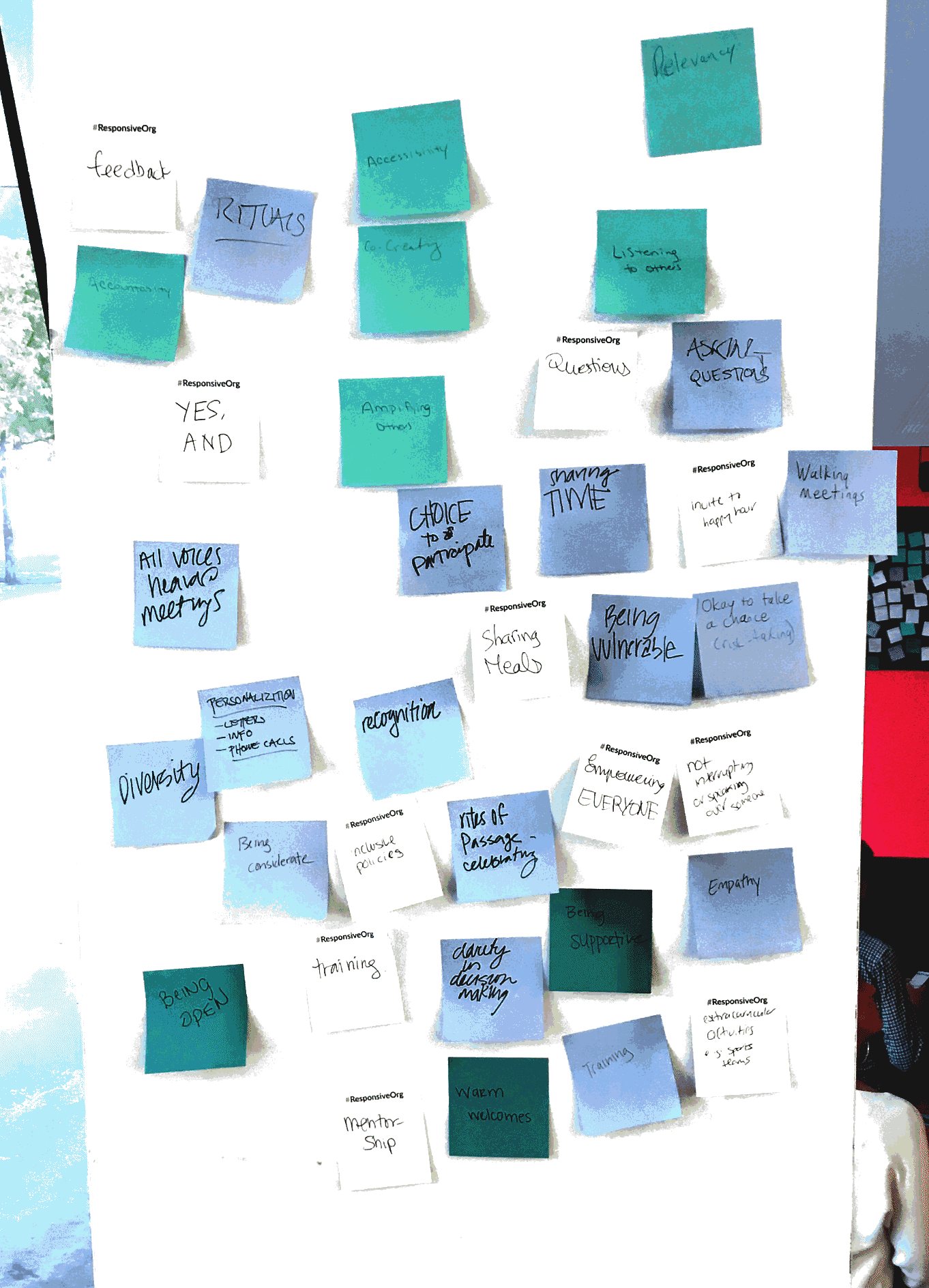

8. We have a human problem. I already mentioned The Human-Centered Museum, the theme of MCN2016, but this is such an important point about modern workplaces. Business tech blogger and startup founder Anil Dash was interviewed on stage to start off day two of the conference, inveighing against tech companies which didn't practice a basic respect for human realities, citing the recent Equifax breach as a perfect example. He added that many algorithms which have made tech companies huge profits have already accomplished some of the political atrocities which many staffers in the museum community have joined in fighting against—noting that the Muslim registry which the current president wants would be easy to collate from the data sets of Facebook and Google. The same goes for inclusion in tech—Facebook, Dash said, would rather simply gobble up What's App than pay for the coding training which Facebook has claimed is missing in people of color in the tech field. He marveled at how lawyers and doctors and even business leaders are required to take ethics classes during their education and have licensing boards to report to, but tech leaders have neither. Apps and software, he said, are not neutral. Being human at work was the subject of a later workshop I did with Andrea Robb and Kate Shaw, Director of Talent Design and Director of Learning, respectively, at Airbnb. A huge number of participants broke into groups to talk about times at work we felt alone, welcomed, part of a group, or even pressured to join a group when we wanted to be alone (when we wanted a chat rather than pounding drinks at happy hour). This seemed especially relevant for discussions of cultural fit, exclusion, and burnout born of loneliness.

8. We have a human problem. I already mentioned The Human-Centered Museum, the theme of MCN2016, but this is such an important point about modern workplaces. Business tech blogger and startup founder Anil Dash was interviewed on stage to start off day two of the conference, inveighing against tech companies which didn't practice a basic respect for human realities, citing the recent Equifax breach as a perfect example. He added that many algorithms which have made tech companies huge profits have already accomplished some of the political atrocities which many staffers in the museum community have joined in fighting against—noting that the Muslim registry which the current president wants would be easy to collate from the data sets of Facebook and Google. The same goes for inclusion in tech—Facebook, Dash said, would rather simply gobble up What's App than pay for the coding training which Facebook has claimed is missing in people of color in the tech field. He marveled at how lawyers and doctors and even business leaders are required to take ethics classes during their education and have licensing boards to report to, but tech leaders have neither. Apps and software, he said, are not neutral. Being human at work was the subject of a later workshop I did with Andrea Robb and Kate Shaw, Director of Talent Design and Director of Learning, respectively, at Airbnb. A huge number of participants broke into groups to talk about times at work we felt alone, welcomed, part of a group, or even pressured to join a group when we wanted to be alone (when we wanted a chat rather than pounding drinks at happy hour). This seemed especially relevant for discussions of cultural fit, exclusion, and burnout born of loneliness.

Because there are always stickies … (image above from the workshop by Andrea Robb and Kate Shaw, on how Airbnb put staff first in their internal culture)

9. People out there love the museum field. I didn't meet a single person at the Responsive Conference who didn't love museums—we were meeting in one, after all—or love mission-driven institutions. But they understood the difficulties museums were having in a distracted age, in an age where people aren't so sure they want to be members, and where technology and legacy practices collide on a seemingly constant basis. We in museums have a lot of supporters out there, especially in new fields like organizational culture, and it would be a shame if we didn't try to bring them in the building, or go out to where they are. The day after the conference, about 25 people—a mix of museum professionals, friends-of-museums, org-culture professionals, and interested parties, met in an Upper West Side bar as part of the monthly Drinking about Museums NYC gathering. Under the organization of Drew Radtke, I worked with responsive org company August to gather the group together, and we had no problem filling up a room with both sides of the cultural org-org culture divide. As I told the group, the museum field needs org culture people, and org culture needs museums. Even if it's not happy hour.

*The museum tech field is filled with glorious weirdos, so we're good!* (A slide from Pam Slim's deck)

*The museum tech field is filled with glorious weirdos, so we're good!* (A slide from Pam Slim's deck)

10. What Am I Going To Do Tomorrow? I end with this motivational exercise from the conference's closing thoughts, presented by conference director Robin P. Zander. He asked the attendees what they were going to start tomorrow—and wouldn't settle for a vague answer. (I didn't raise my hand, ahem, and I'm not sure I acted on something inspiring the next day—blogger, heal thyself.) He asked, what do you need to do to get out of your own way? To show up?

Indeed, that's the (shameless plug) of the all-day series of sessions I organized for MCN2017, called "#MCNergy: What I'll Do When I Get Back to My Museum." It's the reason the theme this year not just "Looking Back, Thinking Forward," but "Taking Action." It's why we're all getting nuts internally, because we see the need for change—and know the arguments for stability—but know we're never going to get anywhere if we just keep doing things like we are. That means asking some very tough questions about just what "doing things like we are" means—very likely, more about our own racial, educational, and class privileges, and how far we need to go to fulfill our mission to our audiences and communities, and each other, than we might care to admit.

Get ready to light this up.

Bonus point

It's only 79 days and counting until The Last Jedi!

What I'm Reading/Listening to

- Emergent Agenda, the podcast of responsive aces August, which I've been bingeing on recently! You get to know a lot of the people there through their stories of working in the field, in addition to the nature of their work.

- Thinking Fast and Slow, by Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman

- IDEO Futures podcast

- Harvard Business Review's IdeaCast podcast

- One Small Step Can Change Your Life: The Kaizen Way, mentioned above, by Robert Mauer, Ph.D. Since I first started this post I finished the book and while the description of breaking down large problems into small bits is sound—and practicable—the anecdotes seem a bit dated, and, in the example of the "broken-windows policing" policies of former New York City police commissioner William Bratton, quite problematic.