A series of blog posts from the Getty detail just how deeply digital practices have been woven into museum work. What will it take for museum professionals to keep up?

You might not have seen it back in December, but over the holidays you could have skipped bingeing on Netflix and instead read an omnibus series of posts at the Getty's blog, the Iris, which examines in amazing depth and breadth the importance of metadata and other digital underpinnings of modern museum content.

This is more than just the old debate about digital versus traditional art books, or allocating resources into mobile and web versus on-site visitor experience. (The fact that these oppositions really don't even make sense anymore is telling.) The fact is, if you've done anything the technological underpinnings of your museum's content, in the past couple of years, these blog posts detail the "oh, shit, yeah, that" moments that drive you nuts.

Go go Getty digital!

For me, as a sort of print technologist, a list of digital "gotta do that" items (meaning the things just a little too far down the Post-It™ note of the day's tasks to get to) includes:

- archiving files for completed print publications without simply dumping them en masse into yet another shoebox … oops, I mean, server

- figuring out which high-res images should be archived—raw captures, slightly color-corrected, color-corrected-for-a-specific-printer, and in which format

- exporting text from final print publication or object label files in a format that curatorial or other staff can use, and doing so in a workflow that's efficient and not horribly time-consuming and doesn't have you dreaming of a world in which every colleague had their own copy of InDesign …

- advising on just which digital format would work for content re-used from a print publication, and why

Like all good articles on tech and content, the Getty series is about the practice of digital, not just the workflow. Since technologies always change, the way to get ahead of the curve is to bake better habits into the way we work. And the wider these behaviors are adopted, the better.

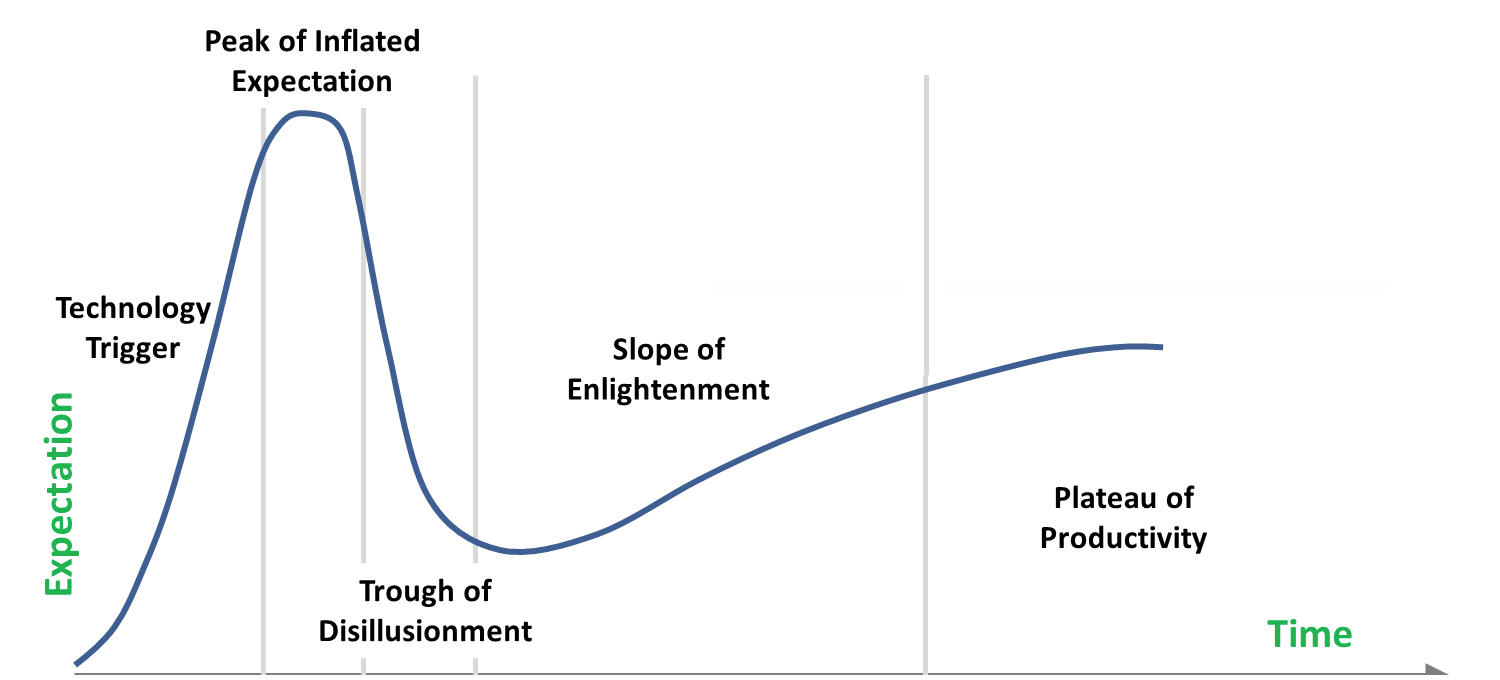

You are (somewhere) here (image credit)

Unfortunately, that's where messy reality, AKA the "Trough of Disillusionment" comes in, usually at the point of selling your colleagues on extra work or having to take on that extra work yourself.

As a former aspiring traditionally-published writer (and a more recent aspiring self-published writer), I've read plenty about the importance of metadata in the self-publishing community. Anyone starting a blog sees a lot of attention paid to SEO, and Google Analytics can go from basic to not-so-basic pretty quickly. "Discoverability" is yin to the yang of producing quality content (in the museum field, think visitor experience and excellence of collection).

To quote Butthead, "Uh … words"

In the content world, whether print, digital, or hybrid, you have to get the word out to the people who are likely to want to read it. (Getting the word out to everyone, whether, for writers, "my potential readership is everyone who likes a good story" or, for museums, "the public needs to know about this kind of art or art-related activity," is vanity in publishing and noble for museums, but provides less ROI and thus needs a lot of willing institutional support for mission-driven content.)

Considering the discussions fostered by the Museum Computer Network 2016 conference theme—"The Human-Centered Museum"—it was heartening that one of the Getty pieces was called "the human dimension of metadata" and another "making meaning from uncertainty." The Getty, by showing their work and opening up their great blog to so many people across their (front- and back-end) content spectrum, has done a huge service to the museum field. Every institution should show such unity around a single concept in order to demonstrate how different people around the institution are really working on the same thing.

The question is, can we afford to do all the necessary grunt work? It's not the writing of the blog posts that we hate, it's all the other stuff that goes into feeding the WordPress cookie monster, which is why I switched to doing this blog in Ghost, and it still takes plenty of work to add relatively simple bells and whistles to a theme.

As we advance through our increasingly-digital museum careers, what percentage of our work is now "digital, other": the scut work (to use the medical term) that keeps everything organized and chugging along? Who isn't doing more work that used to (not-so-fairly) go to interns or more-junior staff?

Just another day in content-land (image credit)

As museums become increasingly concerned about resources, they have to ask more directly about the sustainability of even the most prized and precious digital projects (or non-end-digital projects with significant digital needs). Even the most automated of solutions will take time and resources to develop because, after all, an archiving solution is not exactly sexy, even when it's a matter of preserving what could be the most important data in the world.

Medium-not-so-well?

Look at what's going with Medium, abandoning their attempts to make sustainable bank from an ad-supported elite-publication model, even as it gave the rest of us a really nice content-creation experience at the modest cost of granting non-exclusive rights to Medium forever. Said abandonment also meant firing a third of their staff.

Medium's next step? Find a new model. Uh … good luck, let us know how that goes. And I'm not being cynical here—maybe Medium can do it. But no one has figured out yet how to produce great content without either burning through venture capital money or churning through staff and freelancers. We have yet to find the fabled city of cheap-to-produce content that makes lots and lots of money without resorting to endless wars between algorithms of cheesy advertising and blockers of said ads. I love Medium and yet I acknowledge the fundamental content paradox (which I made up but is probably many places across the Interwebz):

content costs x to produce1 but the world will pay about 10%2 of x for it

1: add in all time, effort, opportunity cost (other stuff you could or should be doing), learning, and frustration to produce this content, even if (perhaps especially if) it's a free, "views-my-own" blog

2: YMMV, somewhere in between the success stories of some subscription-based content and the vast majority of free-to-read blogs

So until we have Star-Trek-level computers basically managing themselves (except for the occasional level 1 diagnostic) or Star-Wars-level 'droids doing all the scut work, or perhaps we all leave our physical bodies and become singularity beings of pure software, we have a who'll-pay-for-the-work-to-make-the-content problem, and all the manifestos in the world won't make that go away. In nonprofits like museums, where mission-driven means, to many of our colleagues, "well of course no one's going to pay for it (and why should they?)!", this dilemma is even more acute. For museums, that might mean tapping our Development departments for Donors for Scut Funding (do ordinary blog writers have resort to a ScutStarter™ campaign?) or just writing it off as the new cost of doing new business. Neither prospect exactly gets us, not to mention our senior staff, salivating.

So, on that note, please check out the great Getty series, and please tweet me with your thoughts on metadata and other digital realities that are inflating your workload.

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this post please spread the word!