Museum workers need comprehensive digital skills that are fairly and equally distributed. Will we end up with digital haves and have-nots in the museum?

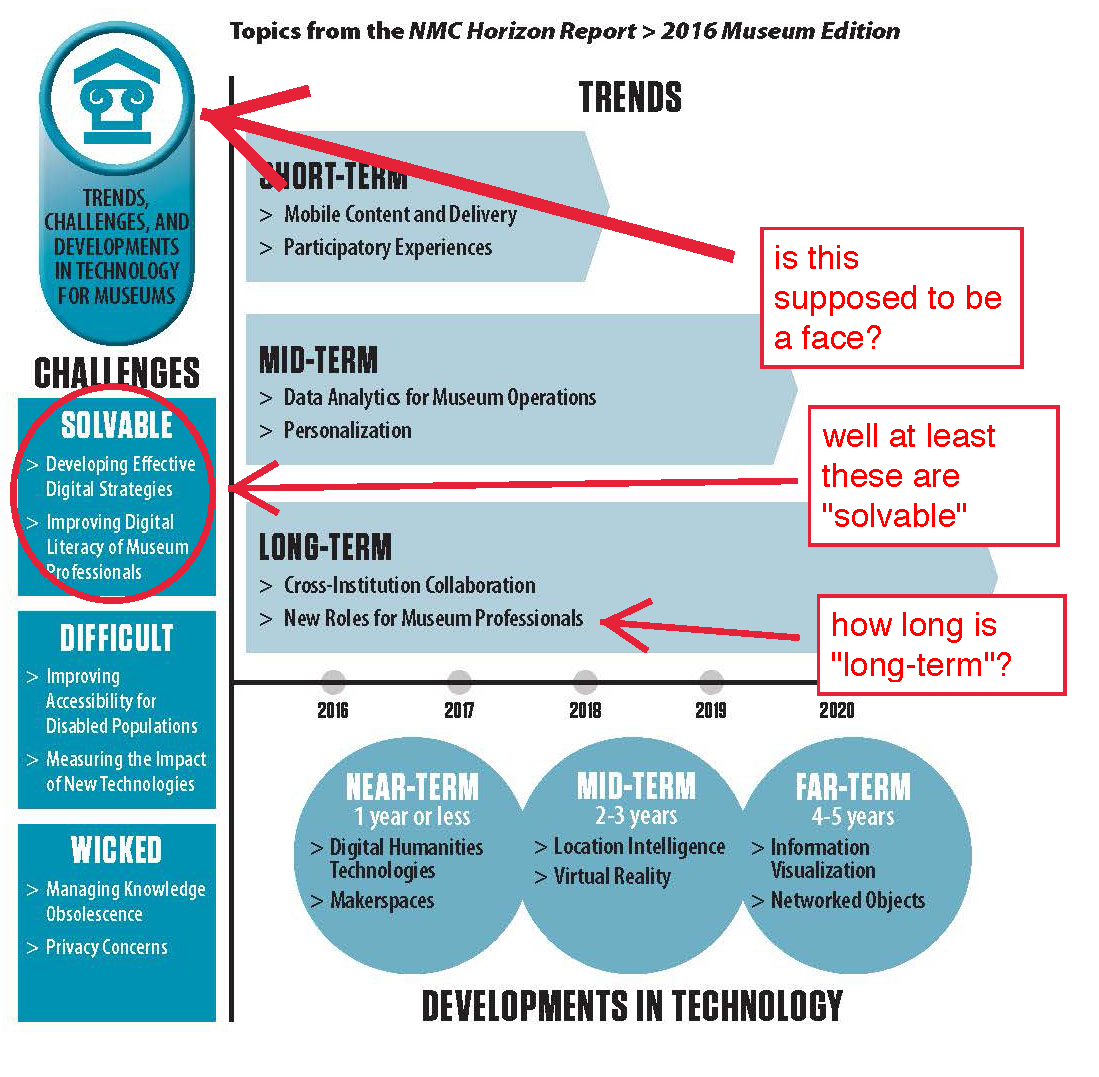

The annual New Media Consortium's Horizon report focusing on museums is always an interesting read, even if it's a bit of a time warp: by the time you're done, half of the technologies might have already changed their time frames. That doesn't make the document any less useful, but it means that you have to read it with less of a grain of salt and more of Hermoine's time turner. YMMV.

Museum future, in handy chart form. YMMV. (From the NMC Horizon museum report, page 8, annotations mine)

What I especially like about the Horizon reports is the emphasis not just on technologies but internal changes in museums. Smart digital departments and leaders have been telling their institutions for years that digital skills are for everyone, just as accessibility and visitor experience aren't the exclusive province of education and visitor-service departments. (Is it the museum equivalent of the corporate-culture dictum, "Everyone here takes out the trash"?)

The section "New Roles for Digital Professionals" has positive examples of museums taking charge of this process. But just as politicians always go on about job retraining for workers in vanishing industries, it's one thing to talk about re-creating Silicon Valley in Coal Country (or maybe Solar Valley?), another thing to actually do it. To quote the report:

The growth of digital initiatives requires the continuous development of digital literacy … . Some leaders in the field argue that in addition to assessing the needs of the community and training staff, museums need to employ a service design approach when creating transformative, visitor-centered digital initiatives. This shift involves staff becoming more aware of the museum’s collection of systems, cultures, values, and processes holistically in order to move an organization beyond silo-based, project-oriented thinking. (NMC 2016 Horizon museum report, p. 10)

In the museum, there are visitor-service departments and there are curator-service departments. Sometimes the two intersect, sometimes they don't. We've seen financial and cataloging systems not always achieve desired results because staff don't understand how to use them—and this isn't entirely the fault of IT departments. Staff have to want to learn to use them, and they have to understand why they should want to. Digital literacy in the museum has to be a virtuous circle of management setting priorities and explaining them, IT implementing intelligent systems and training structures, and staff learning the new systems in good faith.

Well, to quote Han Solo in the first Star Wars movie, that's the trick.

I think back to a staff symposium at the Met earlier this summer, on the evolving digital roles in cultural institutions, and an appearance by Kate D. Levin, who heads up Culture Assets Management for Bloomberg Philanthropies and was Director of Cultural Affairs for the 12 years of Michael Bloomberg's mayorship.

Levin is a strong believer in making museum experiences more participatory. (The NMC report mentions Bloomberg Philanthrophies' $17 million award to six New York museums to expand its Bloomberg Connects program.) Which is fine, funding is good. I love funding.

But while we debate excellence-of-collection-versus-visitor-experience, real digital literacy burns. We hire smart people to set up new systems but don't explain to all staff why these are important or don't implement them in a holistic and thorough way. In addition, we don't factor in the extra work involved in increasingly technology-driven museum fields (as in, all of them). A colleague in a technical museum field expressed this to me recently: we don't have the time to serve the curators, she said, and also stay current in our field, learn new techniques and technologies, understand those technologies enough to purchase them effectively, and just do our jobs in service of the collection.

Hermione, where are you with that time turner?

It's more than just tech training. Museums and staff have to be responsive and open to shared practices and understandings of what it means to be technically trained in museum work. Digital literacy is a cultural shift, not just knowing how to use a couple of programs. That's what will let digital departments, and the technologist staff members sprinkled elsewhere around the museum, spend time on the amazing projects only they can do, and not just supporting their colleagues.

The bonus challenge here is not just time to do it all, but budgets as well. When all museum staff know how to use computers and are up-to-speed on what's going on in their field, and can visualize interesting and important projects to take on with their colleagues, some funny things might happen. Said staff might want to do things with this knowledge. And things cost money (and time, and since time equals money … math.)

I don't know, have you tried Lynda.com?

Are museums ready to work this time/money into their budgets so that the digital literacy everyone agrees is important can actually accomplish something? Collections don't digitize themselves (there's an interesting application of the "Internet of Things"), publication archives don't pack themselves into boxes to send to offshore scanning vendors, and so on. (And no, "more interns" is not the answer.) Many museums are experiencing budget concerns, but cutting every use of these newfound and newly-hired skills sets and the staff they came in with will not only bring many new ideas to a halt, it will breed the kind of cynicism that might take longer to repair. If staffs are cut, will digital skills atrophy?

This post about "museology" (think "museum practice"), from a long but worthwhile series of posts, says it very well:

in an “in-digital” or “post-digital” hybrid museum, or however else one wishes to name it, museum technology is important. But the museology of its technology is more important. Technology may be the means and not the end, but the means potentially shapes the course towards the end.

Technology is really a symptom of museum practice. As stated in the NMC Horizon museum report:

Some museums are already breaking new ground, moving beyond the familiar territory of preserving and interpreting objects in their collections to exploring their potential as social change agents." (p. 10, emphasis mine)

In a change-ready institution, a little tech training and implementation can go a long way.

Multiple essays in the recent CODE | WORDS "Technology and Theory in the Museum" collection on Medium (reviewed in this blog here) discuss how technology can improve practice inside the museum, treating digital skills as an important and necessary part of openness and self-governance. (Read especially the pieces by Janet Carding, Bridget McKenzie, and Mike Murawski.) Better tech skills all over the museum lead to a better workplace environment for all.

What I'm worried about isn't technology in the museum per se, nor even how to teach staff to use tech, but tech's reach and equality and fairness, so that everyone on staff is using it to the same essential degree and effect, and that there aren't pockets of Luddism opposed to high-end Lab experimentation. "We're all in this together" is critical when we're talking about internal technologies, because the last thing we can afford in the budget-stressed museum field is to have our own digital haves and have-nots.