Are museums ready for what real diversity will entail?

(The views in this article are mine and don't reflect any specific policies of any institution.)

One of the most compelling reasons to talk about empathy in a museum context is that empathy can be a gateway drug to so many other conversations. The most pointed, perhaps, is the subject of diversity.

The Met, like many museums, has been looking to make racially diverse audiences feel more welcome at the institution. Earlier this year, a New York City teen made headlines for getting her art on the walls of The Met (watch a video about her here). Other NYC public school students whose works were judged by The Met were honored on Times Square billboards as part of a program where art made by city kids become a part of The Met, if only for a while.

An outstanding blog post by Mike Murawski, the Portland Art Museum's Director of Education & Public Programs, looks at how empathy can help museums converse with many racially and ethnically diverse communities, to confront the realities of violence and discrimination in our civilization. He cites endeavors like The Empathetic Museum and The Incluseum as examples of how museums' relationships to their communities can improve museum practice, and he lays out out a riveting case for what museums need to do to better serve all their visitors.

Now, no one is a bigger fan of empathy than I am (see posts on the subject here), but empathy can still be a surprisingly tough sell inside our institutions. As Suse Cairns, until recently the Director of Audience Experience at The Baltimore Museum of Art, pointed out during a twitter conversation related to Murawski's article:

@murawski27 @robertjweisberg Most people who work in museums surely are empathetic. Why doesn’t that translate into institutional structure?

— suse cairns (@shineslike) July 12, 2016

Cairns linked to her 2013 article which discussed the limits of empathy in reforming workplaces. Cairns isn't anti-empathy, but she makes important points about what's realistic in museums as workplaces.

Douglas Hegley, Director of Media & Technology at Minneapolis Institute of Art, added another observation about the distinctions between museums and their staffers:

@shineslike @murawski27 @robertjweisberg OH: #museums are mostly staffed by liberals but the orgs act conservatively. Hill to climb?

— Douglas Hegley (@dhegley) July 12, 2016

For now, empathy can only go so far in reforming our current museum environment:

@robertjweisberg @dhegley @shineslike @murawski27 When empathy feels risky/alienating we know we're in trouble. Museums, we're in trouble.

— ExposeYourMuseum LLC (@exposyourmuseum) July 13, 2016

If museums want empathy to really take hold, there's no short cut to addressing diversity within the institution. While many museums actively reach out to diverse local communities for interns, even internships are fomenting lawsuits like at the Getty (here and here). Looking to internships as some sort of internal diversity pipeline has its own challenge: where entry-level salaries are low, intern stipends are often non-existent. In urban areas with high costs of living, having well-off parents is well-nigh indispensable.

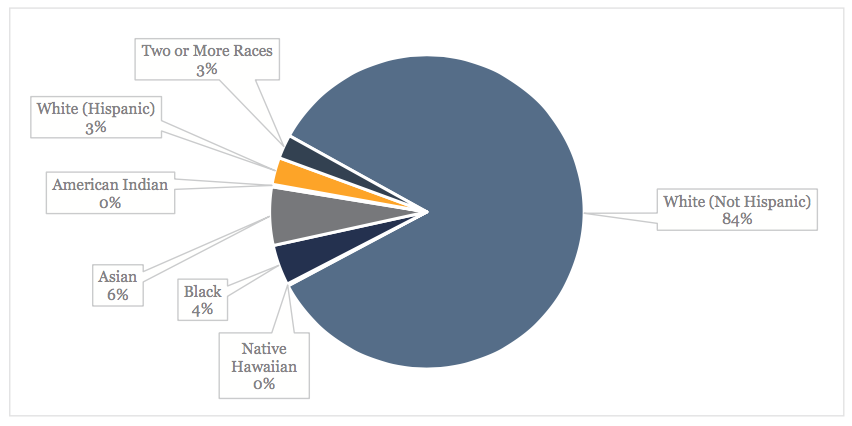

The situation grows more fraught the higher up the org chart you go: college and post-grad interns, all the way up through staff, managers, department heads, and directors. Last year's Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey (with valuable discussions here and here) was explicit about what it calls a "youth bulge," even as women have become the majority of museum staff members:

there is no comparable "youth bulge" of staff from historically underrepresented minorities in curatorial, education, or conservation departments.

Race and Ethnicity in art museums (Curators, Conservators, Educators and Leadership Only), from the Mellon study

The Ford Foundation and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs are also speaking out and studying the racial diversity of museum staffs. But so far, those efforts seem to be paying off more on museum boards than across the institutions.

Many groups are actively discussing the whiteness of the museum field and its impact on society. The #museumsrespondtoferguson hashtag has done much to push the debate. The group Museums & Race held a gathering, "Museums & Race 2016: Gathering for Transformation and Justice," during the annual American Alliance of Museums conference in May (read this Hyperallergic follow-up). During the same weekend, an event called CrossLines ("A Culture Lab on Intersectionality") took place at the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center (reviews here and here) and many conference participants attended.* The Museums and race project and this excellent blog post by Rebecca Herz called have contributed further to this conversation.

(In a previous version of this blog post, I wrote that the Museums & Race gathering and the CrossLines event were sidebar parts of the AAM conference. This was incorrect, as both were independent events. Citing them as sidebars was sloppy on my part and serves to emphasize how much work "the default" in the museum field has yet to do to break our habit of minimizing our responsibilities to act.)

But, to draw an analogy to the civil rights movement, the people who really need convincing about the diversity problem within museum staffs are the ones already in the building. Here's Malcolm X, famously rethinking his response of "nothing" to a white woman who asked “What can I do to help further your cause?”

By visibly hovering near us, they are "proving" that they are "with us." But the hard truth is this isn't helping to solve America's racist problem. The Negroes aren't the racists. Where the really sincere white people have got to do their "proving" of themselves is not among the black victims, but out on the battle lines of where America's racism really is — and that's in their own home communities; America's racism is among their own fellow whites. That's where sincere whites who really mean to accomplish something have got to work. [emphasis mine]

(pages 383-84, The Autobiography of Malcolm X)

It can be hard to convince museum staff members—especially those working in expensive urban areas where friends, family, neighbors, and classmates from elite colleges might be pulling in six- or seven-figure incomes in law, on Wall Street, or, increasingly, in the tech sector—that they have privilege that needs to be checked. But an excellent article in Jezebel, written by a former college-application-essay-writing-tutor, and a New York Times Magazine article about the dilemma well-off African-Americans face in not wanting to abandon public schooling, both address a society that practically screams at parents to take advantage of whatever elitism they can, societal considerations be damned. As Nikole Hannah-Jones writes, “True integration, true equality, requires a surrendering of advantage." [emphasis mine]

Many research-oriented fields such as museum work look to interns returning again and again at ever-higher levels, perhaps after graduation, perhaps as a fellow working on an exhibition. And just like with raising "the best" children, nothing, including hiring policies which might bring in new faces and voices and experiences, is supposed to threaten the excellence of scholarship about a museum's collection. The perception of excellence can itself become a cultural fit.

You know another cultural fit that's gotten some attention lately? Silicon Valley. Many of us in the non-profit and arts sectors sneer at tech "bros" and the lack of diversity in the Valley, where "cultural fit" is often a smokescreen for not wanting to hire people who aren't exactly like everyone already there. Just ask Leslie Miley, the former chief engineer at Twitter, about its hiring of a new chief of diversity.

The so-called "pipeline problem" can't be used an excuse in the museum field, any more than it should be an excuse of Silicon Valley to blame society for the lack of diversity in tech. I fully understand that that students in museum-studies programs are already facing a challenging job market. Still, people aren't oil.

![]()

They also have a "pipeline problem." (The cast of TV's Silicon Valley)

The museum is the nexus by which we (the staff) interact with our community (the visitors). We can better do that by making sure that these communities are represented in our institutions, on our staff, to help guide us and the collection. The stakes for our visitors, and ourselves, have never been higher.

The twitter conversation I mentioned above, which started about empathy and led into questions about diversity, ended with thoughts about next steps beyond the usual conference presentations. The Association of Art Museum Directors says that it understands:

@murawski27 @shineslike @robertjweisberg It's a priority for us. Empathy is inextricably linked to creating a more diverse & inclusive field

— Art Museum Directors (@MuseumDirectors) July 12, 2016

@murawski27 @shineslike @robertjweisberg our last meeting focused on this (if indirectly) - e.g. training to recognize unintended bias

— Art Museum Directors (@MuseumDirectors) July 12, 2016

Through empathetic approaches, museums will not only become more internally aware of racial bias, but sensitive to age diversity and issues of class. Even having a diversity of previous experiences—art history, museum work, tech, etc.—may help museums speak better to the modern experience faced by all kinds of communities.

If true diversity is going to become part of museum practice, if we're going to move past our current cultural-organization echo chamber, it's going to take a lot of work and a lot of time. That's why they call it "practice." It's a huge undertaking, which is what makes it worth doing.

Follow-up note: Just after I posted this piece, I read this article in The Art Newspaper (via a link from Blouin Art Info), which mentioned the study by the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and an ensuing commitment to spend "$1m to support diversity efforts among city-subsidised institutions, ranging from the Metropolitan Museum of Art to the Bronx Historical Society." One proposal being considered is replacing unpaid internships with the paid variety, though it's not clear from reading how this would be implemented. The article, which also quoted one development officer based in NYC who felt the more funding should be directed towards existing multi-cultural organizations rather than trying to add token diversity to already-funded large institutions, is a must-read.

PS: If you've made it this far, please check out my follow-up to this post.